12/05/2014

blog A Brazilian Operating in This Area

Brazilian elite uses the World Cup to show their discomfort in being Brazilian

Mauricio Savarese

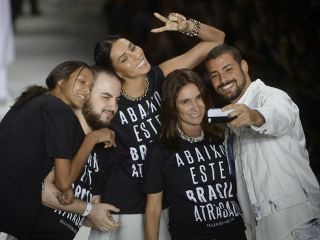

“Down with this underdeveloped Brazil.” That is how jeans-wear Ellus decided to engage with the World Cup — by putting that message in a shirt. I suppose they have a lame PR response, saying it is against the bottlenecks, not against the country. Still all Brazilians who understand our stray dog syndrome know what people who wear that shirt actually mean. After all, Ellus stores are attended mostly by folks who don’t use the public healthcare system. They don’t study at state schools. And they rarely set foot into public transportation in Brazil’s main cities (although they gladly do it abroad).

So what are they frustrated about? Are they as selfless as the activists who protest with an end in sight, whatever that end is? Or do wealthy Brazilians voice their criticism out of sheer boredom?

My answer is that rich Brazilians are frustrated for being Brazilian. And they poison the tone about Brazil hosting the World Cup more than the mistakes and bad planning in the run-up to football’s extravaganza. I know it isn’t exactly news for anyone who has been in a Brazilian party in Jardins or Leblon. But this is probably a good moment to point that out.

Some elitists deal with that upsetting reality of being Brazilian in a proactive fashion: they get an European passport, as if they were one of those who really have a family bond abroad. Others choose to target symbols that are linked to the country they reject. That has been done before. Samba, country music, feijoada and all things Brazil are either discarded or twisted into a gourmet version that fits the elite’s allegedly better taste.

Football has somehow been in the middle of the road — one can’t disbrazilian football. But now European clubs are more and more popular here. Perhaps that shows the attention is shifting in that area too. It would be a good reason to explain why World Cup criticism, which was very irrelevant not long ago, gave the Brazilian elite an opportunity to express their annoyance.

“Dear foreigners, please, don’t come to the Brazil World Cup because we can’t protect you from the people we hate. Wait for us to visit you, please.”

The June 2013 protests changed the landscape for Brazilian elites. After transport fare protests became a national wave including very different kinds of people, rich Brazilians became very vocal for the first time in a long time. It was their time to show their presence after years and years of frustrating movements. They used the legitimacy of the initial protests to make it sound as if we were all on the same boat. The World Cup one was surely a great link.

World Cup spending only got in the equation after the movement exploded. Although preparations surely deserve criticism, it was only one year before kick off that our elite discovered this could draw more attention to all they dislike about Brazil. Suddenly they made Brazil look as undemocratic as North Korea, as poor as Paraguay, as chaotic as India, as careless about human rights as Saudi Arabia, as corrupt as Russia. Brazil has surely bits of all of those, but is very different from all of them.

Even if Brazil were like that, our elite would have to do soul searching, not finger pointing. Of course there are exceptions, but wealthy, schooled and well traveled anti-World Cup social conservatives aren’t very keen on sharing the country that got the World Cup basically because it started sharing its profits with the poor. The fact Brazil has spread some wealth in the last 20 years doesn’t sit well with rich kids who hear their rich grandparents say great things about those years of the military rule. Some say they identify with the opposition parties, but it is merely a matter of taste: in substance, the ruling Workers Party isn’t very different from the Brazilian Social Democracy Party.

Unsurprisingly, these are the same who advocate for changes that, essentially, give a harder time to anyone out of their league. They want to put under 18s in jail, to get more active policing, to make corruption a heinous crime (only for officials, not for those who bribe them) and so on. Among those people you can also find critics of measures to bring foreign doctors. Others are the very doctors who refuse to work in poor communities — they want to earn more working as dermatologists in big cities. I can’t see European, American or Asian elites being so self-absorbed. It is probably a Latin American thing.

What better symbol for the Brazilian elite to channel their frustration with Brazil not being what they want than to hammer the football World Cup, the event that makes the country stop every four years? Support for Brazil hosting the tournament has surely dropped in the last year or so, but it is the platitudes spread by the rich Brazilians (sometimes in English) that are getting time in the limelight as if these guys lived through the grievances they address. Truth is they don’t even care about them. Many are kidnapping the very social agenda they disagree with to make shallow and politically disengaged criticism.

That is a often a disguise for their discomfort for being Brazilian, unlike criticism from those who give a meaning to their antagonism.

Mainstream media has picked on that elitist rejection and amplified it. Videos like Carla Dauden’s boycott offer are used to show there is a nationwide bad vibe. But that is the feeling of the “upper middle class”, as they like to define themselves (FYI: apparently there are no rich people in Brazil. That Human Development Index map below might disagree, but who cares?).

Hosting the World Cup, which was meant to be a pinnacle of social inclusion, is being twisted into a mere “we spend too much, get too little” event. The tone used by the wealthy Brazilians isn’t “this needs fixing” — most of them know too little of politics to actually engage with substance. Their message is “screw all this” (as Carla Dauden’s boycott video suggests). It seems the underdeveloped Brazil deserves to be embarrassed by the perpetrators, not by the victims. The latter are critics, but not ashamed of their country.

Elites who criticize the World Cup in Brazil have used well a great chance to show they don’t relate to football as everyone else — they sold the idea that those engaged with the World Cup are actually disengaged with Brazil. They show themselves as agents for real change, when they are quite the opposite — just look at their other suggestions and you will see Brazilian elites couldn’t care any less about people being evicted because of new stadia, for example.

I am no Marxist. But it is difficult to defend one of the most narrow-minded elites in the world. Many foreign journalists who spent long enough here will second me on that. Brazil’s favelas somehow remind our tiny, white and sometimes religion-crazy rich people that they had the keys to slavery. So they slam the World Cup being played not far from those. On the hills of Rio and São Paulo suburbs, there are hundreds of thousands whose great grandparents couldn’t be hired because master wouldn’t buy his property again by giving him a contract.

These Brazilians don’t blame only the organizing committee for World Cup construction delays: they pin it on builders for being slow and ineffective. That’s how they satisfy their fetich with poor being responsible for their poverty. Brazilian elites very often see a black person as a potential maid or a driver. If they don’t get that glass of orange juice at 8 am, it is probably because these poor folks are just a bunch of lazy ungrateful people. “Typical Brazil,” one of those told me once at an interview in a hotel.

(Not very different from what The Economist recently suggested in a very poor comprehension of Brazil’s complexity.)

Congressman Romário voiced many elitist perceptions in the run up to the World Cup. Now he profits doing World Cup ads.

Large chunks of the media revolve around that tiny elite for their stories. Although there are activists with reasonable concern for human rights and better services for everyone, most of the message has to do with what wealthy Brazilians can express in English. That’s how they got known: by whining about things they don’t understand in Brazil. (See the case of Arena Corinthians. It sits in a poor region. Many elitists say they won’t go because it is “an ugly part of the city”.)

That shirt by Ellus is a great example of an old standard of the wealthiest Brazilians: they pretend everything that is wrong with Brazil has nothing to do with them. Corruption doesn’t start with their companies. Inequality doesn’t come from they paying less taxes than everyone else (and they still dodge fiscal laws). Crooks have never been elected or financed by them. The underdeveloped parts of Brazil are not to be dealt by engaging with politics and putting solutions forward — their idea is to prove their success comes exclusively through their effort. Everyone else’s failure is not theirs.

It is difficult to predict whether they will have success in shaming Brazil till the end. Protests are more measurable than their dissing. Whatever is the legacy of the World Cup, I just hope that the underdeveloped Brazil beats their haters. I come from the underdeveloped Brazil. If the World Cup were our biggest problem, it would be great. If the World Cup isn’t a success, I will be here to report it as it is. But I am hoping it will. Not only because of previous experiences in big sporting events. It is because I want to see people who wore that shirt eat their words very soon.

Down with Ellus!

política

21/09/2022 | Salvar a democracia exige reformas fiscais profundas

19/06/2019 | A classe invisível

20/04/2019 | Previdência, três mitos e um problema

12/10/2016 | 10 perguntas e respostas sobre a PEC 241

geral

03/11/2022 | Jung Mo Sung: Lógica que gerou avanço evangélico é a mesma que leva a seu caráter autoritário

21/09/2022 | Salvar a democracia exige reformas fiscais profundas

21/06/2022 | Estudo quantifica impacto humano sobre a capacidade de retenção de carbono da Mata Atlântica

17/05/2022 | Tecnologia otimiza geração de energia verde pela indústria cervejeira com bagaço de malte

07/02/2022 | O impacto das cotas nas universidades públicas